Social Isolation: Community Solutions

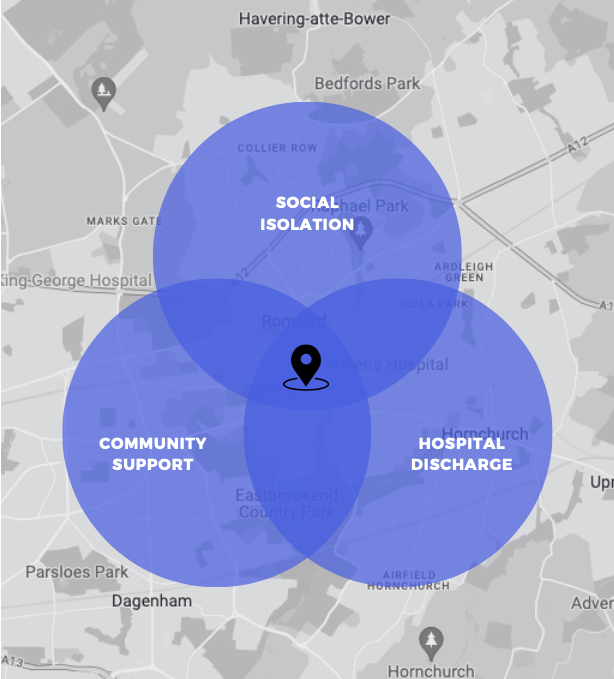

Collaborating with the NHS and local charities in Barking and Dagenham, this project combines individual testimonies, case studies, current research, and diverse interdisciplinary insights to address social isolation in patients discharged from Queen’s Hospital, a key factor in high readmission rates.

Introduction

A challenge in identifying a socially isolated person is that an individual’s needs play a major role in determining their perception of the availability of social support. A person’s reported level of social support reflects the degree to which a person is satisfied that their needs are being met, rather than an objective statement of support itself (Cobb 1976; Thoits 1982; Rokach 2000). To explain this further, if someone is objectively isolated (in the sense that they do not have any social connections within their community) yet they are completely content with this and do not require assistance in any aspects of their life, are they still considered socially isolated? At what point do you intervene and provide support for that person and label them as socially isolated, when in fact that person chooses to and prefers to live in solitude? Do you wait until an event, such as a fall, occurs – addressing the matter only after the person has been admitted to hospital? Or do you intervene prior to this and prematurely strip them of their autonomy and independence?

Already, from this brief introduction, the phenomena social isolation finds itself located within a multi-faceted complex system. By this I mean that, there are clear and distinct components to this problem, yet the problem of social isolation itself can be seen from multiple perspectives – depending on the aim of one’s enquiry. To best understand this problem, and the sub-systems within it, an approach that considers the non-linear relations and interactions between different elements, the multiple and contested goals (that may be of interest to different stakeholders), and the ever-adapting conditions of which this problem operates within, would prove most fruitful when tackling the problem. Given the complexity of this problem, it appears that an interdisciplinary approach would be appropriate when attempting to tackle this problem.

This suggestion is yet further reinforced by the ideas presented within Artime’s and De Domenico’s work on emergent phenomena. They argue that an emergent phenomenon is described as having “at least two well separated scales” (Artime O, De Domenico M. 2022: p3). I would argue that in the context of social isolation, these scales have been identified as the objective measures and the subjective measures. The authors continue to describe how the study of such phenomena “has become more and more an interdisciplinary endeavour” (Artime O, De Domenico M. 2022: p3).

I felt that this section was necessary to include as not only does it set the tone for how the rest of the report explores this problem area, but it also emphasises the need to integrate findings within the fields of both social isolation and loneliness. I stress this point as my initial brief was clear in the sense of only addressing social isolation. However, as I continue to explain further on within this report, I feel there is an overwhelming need to incorporate both elements into the problem solving process. With both elements significantly influencing a successful hospital discharge.

Who is most at risk of social isolation?

The findings of Holt-Lunstad et al. (2015) challenged the assumption that social isolation primarily affects older adults. Instead, the data indicated that middle- aged adults were at greater risk of mortality when experiencing loneliness or living alone. The authors proposed several plausible explanations.

One possible explanation put forth by the authors is related to changes in social networks during the transition from full-time employment to retirement. As individuals reach middle age and retire from their jobs, there may be a reduction in socialisation in occupational and public forums, which were previously sources of regular social interactions. This decrease in social engagement might lead to increased feelings of loneliness and social isolation for some middle-aged adults. For example, a person who was once surrounded by colleagues and social interactions in a busy workplace might suddenly find themselves with more free time and less frequent opportunities for social interactions after retirement.

This shift could be particularly challenging for individuals who had a strong sense of social belonging and support through their work environment. Additionally, the authors suggested that middle-aged individuals who are alone or lonely might exhibit different health behaviours compared to older adults experiencing similar circumstances. Some middle-aged adults may engage in riskier health behaviours or be less likely to seek medical treatment early, potentially contributing to an increased mortality risk – which, with respect to Care City’s project, would translate to increased hospital admittance. This could be due to a sense of invincibility or lower awareness of potential health risks that are more commonly associated with ageing.

On a separate note, another study (Fiordelli et al. 2020 ) found “significant differences in the objective dimensions of social isolation for people with different levels of education”. The study showed that people with a higher level of education showed significantly lower objective isolation when compared to people with a lower education level.

How do we measure social isolation?

Social Isolation can be measured both quantitatively and qualitatively. Quantitative measures are ideal for assessing a larger cohort of people that are exposed to the risk of social isolation. Surveying a population in this way will help to identify people that are objectively isolated, therefore highlighting areas of interest regarding the delivery of support. This way of measuring for social isolation is relatively inexpensive and would have a quick response time. This is ideal for tackling the problem as quickly as possible.

Quantitative Measures:

LSNS

The Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS) The LSNS measures perceived social support received by family and friends. This measurement is used as a means of gauging social isolation within older adults. It was originally developed in 1988 and revised in 2002 (LSNS-R). This led to two additional variations of the scale, LSNS-6 and LSNS-18. The LSNS-6 was developed to meet clinician’s needs for brevity, it is less time consuming to complete and review. Whereas, the expanded LSNS-18 was designed for basic social and health science research oriented purposes.

All LSNS scales assess the perceived support received from family, friends, and neighbours. The LSNS was updated to the LSNS-R to provide better specification and differentiation of family, friendship, and neighbourhood social networks. Both the LSNS and LSNS-R make a distinction between kin and non-kin, but they do not differentiate between friends and neighbours. In contrast, the LSNS-18 does differentiate between friends and neighbours.

The LSNS has been used in both practice and research settings and has been used primarily with older adults from a range of settings including the community, hospitals, adult day care centres, assisted living facilities and doctors’ offices. The scale has also been used with specific elderly populations such as elderly diagnosed with breast cancer, myocardial infarctions and depressed elderly; other specific populations include homosexual and childless elderly. Caregivers have also been looked at as they often become an increasingly important part of the older person’s daily life.

MSPSS

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (“MSPSS”) is a short instrument designed to measure an individual’s perception of support from 3 sources: family, friends and a significant other. This instrument is 12 questions long and has been widely used and well validated. Some research has identified high levels of perceived social support as being associated with low levels of depression and anxiety symptomatology.

To calculate total score: Sum across all 12 items. This total score can also be calculated as a mean score (divide by 12).

Qualitative Measures:

Cultural Probes

What is a Cultural Probe (CP)? A CP is a way of collecting primary data from participants without a researcher present. Typically, a participant will receive an individualised pack containing a variety of tasks and activities centred around the given research agenda.

Cultural probes are often an assortment of various methods aimed at collecting auto ethnographic data, typically containing tasks or instructions bringing a sense of gamification to the research (Marc Stickdorn, 2018).

CPs are usually sent by post to a person’s address, I would also recommend handwriting the envelopes to invoke a greater sense of personalisation. A return address is often included also, my suggestion here would be to assign people working on the project to a set number of people (perhaps 1 researcher to 3 participants is realistic) and build a rapport with the participants prior to sending out the CPs, and so when the CPs are sent out, the researcher’s address can be included within the pack for it to be returned. This would once more elicit a strong connection between both parties.

Why would you want to ensure a good relationship between researcher and participant? The participant is more likely to answer truthfully if they feel they are able to trust the researcher, this would offer more in-depth insights and increase the validity of results. In addition, particularly for this line of work, building a relationship with participants that are socially isolated or lonely will already begin to work on tackling these problems by simply connecting them to the researcher on a human level and not a purely clinical or transactional level.

Note: It is only advisable to give out your own address if a strong relationship has been established, where both sides feel trust. I do not recommend giving out home addresses to wide-scale anonymous surveys.

Why use Cultural Probes?

As there is no researcher present, participants are more likely to answer truthfully as opposed to being influenced by demand characteristics. This will increase the validity of any results and conclusions drawn from the data. Furthermore, this type of exploratory research only requires a design phase and an analytical phase, meaning that the researcher is free to continue with other lines of inquiry whilst simultaneously collecting data from people.

CPs are often designed with tasks that challenge the hegemony and linearity of written text and increase voice and reflexivity in the research process (Butler- Kisber, 2007). An example of a task within a CP may be to plot on a map points at which a person interacts with other people on a typical day. Or perhaps a more obscure task, such as, creating a sound map of a specific area or route, allowing an image to be generated – this is a task that I could see potential use for in this project as it may allow us to identify areas and routes (accessible by foot) that are more appealing to people. A quieter area could then be targeted with initiatives such as group walks, with the quieter areas providing a less overwhelming experience for someone that may be experiencing their first steps out of their home for some time. Resulting in a more pleasant experience that is not too overstimulating, allowing them to build up confidence for other, perhaps busier and unfamiliar, areas.

Why do I think CPs have particular relevance to this project?

By creating a personalised pack, and building a rapport with the participant prior to the data collection process, this individual will inadvertently become connected to another person. This could serve as a way of reducing feelings of loneliness or social isolation, without implementing any actual methods to do so. Essentially, even the act of collecting data can become a way of tackling the very problem it seeks to solve.

Social isolation can come with associated stigmas, such as shame or embarrassment. I believe that CPs are appropriate here as they allow the person to complete the tasks in the comfort of their own home, at their own pace and allow them to share only as much as they are comfortable with. Whereas a face-to-face interview may be influenced by these stigmas and therefore result in an uncomfortable interaction for that person, who may feel as though they struggle to share their experiences.

What’s the catch?

CPs require a good design process, which will take more time and thought than a questionnaire. They also require more in depth analysis, ideally from more than one researcher to ensure that things are not just interpreted from one point of view.

They also require extended participation and attention from the person completing them. To ensure this, it is important to design tasks that are engaging and enjoyable to complete. In addition, realistic time frames should also be set, it would be unrealistic to send out a CP and expect everyone to return their completed packs in a week, people’s lives are busy!

My Suggestion:

I suggest pairing CPs with an interview debrief. Having gone through this process during a separate project, this proved to be the most effective way of collecting rich and enhanced data – giving greater backing to consecutive actions taken off the back of the data collected. A debrief of some description would allow the participant to provide clarity and context to any work that they have produced. It would also create a space for them to share any thoughts and reflections they may have upon completion of the tasks. This also is of particular relevance to this project as a follow up discussion will provide another touchpoint for that person, once more opening the potential for mitigating loneliness and social isolation.

In regards to the design of CP tasks, in addition to ideas presented in the previous paragraphs, I would recommend including a task that encourages collaboration between people – as a way of fostering connections between people that are either socially isolated or lonely. Furthermore, I also believe it would be useful to include a journal entry of some description as this would allow for a solid case study to be built surrounding each individual, giving accurate insights into their perspective on the problem at hand. And finally, CPs are an opportunity to collect data in a way that is more than just written text. Use this opportunity to create tasks that are enjoyable to complete – perhaps incorporating music and arts, creative tasks, photo journals etc… do not limit it to just text, as although text may be more straightforward to analyse, it only provides one dimension to this insight.

In summation, CPs are a great way of juxtaposing the rigidness of formal interviews and standardised surveys. They allow for freedom of expression in more forms than verbal or written communication. They can be used as both a way of measuring a person’s social isolation as well as being used to inform the design of ideas that aim to tackle this complex problem.

Alternative measures

Alternative measures of social isolation suggested during discussion with the Independent Living Agency (ILA) included checking hospital records to see if the person in question has an emergency contact or next of kin. It is likely that if neither is on record that this person is socially isolated. This would be a really efficient way of quickly establishing a cohort if time and resources were a large constraint.

Something to consider regarding this measure would be that some people may have family and friends that are not in this country. Therefore, how do we go about finding this out?

Another variable to investigate in relation to social isolation is how often a person is admitted to hospital for a seemingly low risk reason – such as a cold. If a person was admitted to hospital multiple times for a cold perhaps this would indicate that they do not have the basic support structure in place at home.

Another alternative method of identifying our target population could stem from partnering with the fire brigade. It occurred to me, when reading the literature surrounding this subject, that there may be opportunity to collaborate with the Barking and Dagenham emergency service. Initial contact with the Chief of the fire station confirmed suspicion that they have access to a list of people who are deemed at risk. It is my prediction that people who are at risk of injury due to a fire will also be less socially connected.

If you have got this far and are interested in reading more, please contact me for the full report. The full report includes vast literature reviews, case studies, examples of existing local, national, and global solutions, as well as valuable disciplinary insights.